Anna Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962) was an American diplomat and activist whom US President Harry S. Truman called the “First Lady of the World” for her contribution to the protection and promotion of human rights. She served as First Lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945 during the four terms of her husband Franklin Delan Roosevelt. Eleanor served as a U.S. delegate to the UN General Assembly from 1945 to 1952.

Roosevelt was a member of the prominent American Roosevelt and Livingston families and niece of President Theodore Roosevelt. She had a difficult childhood during which she suffered the death of her parents and one brother. At age of 15, she attended Allenwood Academy in London and was deeply influenced by its principal, Marie Souvestre. Returning to the United States in 1905, she married her distant cousin, Franklin Delan Roosevelt. Their marriage was complicated from the start because of Franklin’s mother Sarah who tried to prevent their marriage, and, after Eleonor discovered his love affair with Lucy Mercer in 1918, she decided to seek fulfillment in her own public life.

She persuaded Franklin to stay in politics after he contracted paralysis of his legs in 1921 and began speaking and performing at campaign events instead. After Franklin was elected as governor of New York in 1928 and throughout the rest of Franklin’s public career in government, Eleanor regularly held public appearances on his behalf, and as First Lady, she significantly reshaped and redefined the role of First Lady.

Although much appreciated in her later years, Eleanor was a controversial First Lady because of her openness, especially her stance on racial issues. She was the first to hold regular press conferences, write a column in a daily newspaper and a monthly magazine, host a weekly radio show, and be the first to speak at a national party convention, and on several occasions publicly opposed her husband’s policies. She started an experimental community in Arthurdale, West Virginia, for families of unemployed miners with the goal of creating a self-sustaining community. She advocated for the expansion of the women’s role in the workplace, the African Americans’ and Asian Americans’ civil rights, and the rights of World War II refugees.

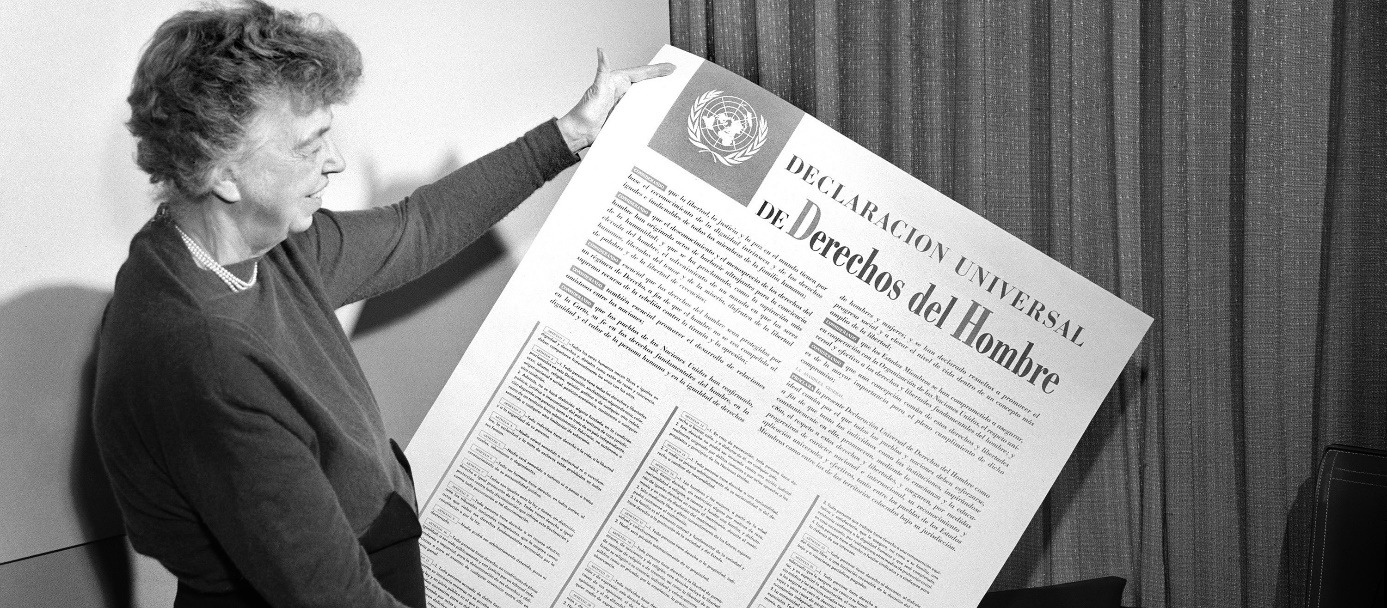

After the death of her husband in 1945, Eleanor remained active in politics for another 17 years. She pressured the United States to join and support the establishment of the United Nations and was its first delegate. She was the first chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights and led the process of drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. She later chaired the Commission on the Status of Women under President John F. Kennedy. At the time of her death, Eleanor was considered “one of the most respected women in the world,” and the New York Times called her “a person of almost universal respect.” In 1999, Gallup’s list of the most adored people of the 20th century placed her in 9th place.

First Lady of the United States (1933-45)

Eleanor became first lady of the United States when FDR was inaugurated on March 4, 1933. As she knew all the previous First Ladies of the 20th century, she was seriously depressed about having to take on a role that was traditionally confined to a housewife. Her immediate predecessor, Lou Henry Hoover, ended her feminist activism when she became First Lady, stating her intention to be just a “backdrop for Bertie.”

With the support of journalist Louis Howe and journalist and friend Lorena Hickok, Eleanor set out to redefine the position of a First Lady. According to her biographer Cook, she became “the most controversial first lady in the history of the United States” in the process. Despite criticism from both Republicans and Democrats, but with strong support from her husband, she continued to actively pursue past jobs and activism that she began before taking on the role of the First Lady at a time when only a few married women had careers. She was the first wife of a president to hold regular press conferences, and in 1940 became the first to speak at a national party convention. She also wrote the daily and widely read newspaper column “My Day”. She was also the first First Lady to write a column for a monthly magazine and host her own weekly radio show.

In the first year of FDR’s administration, Eleanor decided to achieve the same pay her husband had. That year, she earned $75,000 from her lectures and writing, and gave most of it to charity.

In early 1933, the “Army of Bonuses,” a protest group of World War I veterans, traveled to Washington for the second time in two years, demanding an early payment of their veteran bonuses. The previous year, President Herbert Hoover sent a U.S. Army cavalry that attacked them and dispersed them with tear gas. This time, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited veterans at their mud camp, listening to their concerns and sang military songs with them. The meeting eliminated tension between veterans and authorities, with one of the protesters later commenting, “Hoover sent troops, and Roosevelt sent his wife.”

Activism

During the Franklin administration, Eleanor became an important liaison with the African-American population in the era of segregation. Despite the president’s desire to appease southerners’ hunches, Eleanor was all-vocal in her support for the civil rights movement. After her experience with Arthurdale and her inspections of the “New Deal” program in southern states, she concluded that New Deal programs discriminated against African Americans who received a disproportionately small proportion of relief. Eleanor became the only voice in the Roosevelt White House that insisted the benefits of the New Deal should be extended equally to Americans of all races.

Eleanor also broke with tradition by inviting hundreds of African-Americans to the White House. In 1936, she became aware of the conditions at the National School of Girls Training, a predominantly black reform school. She went to school, wrote about it in her “My Day” column, advocated for additional funding and pressed for changes in personnel and curriculum. Her invitation of students to the White House became a problem in Franklin’s re-election campaign in 1936. When black singer Marian Anderson was denied the use of Washington Constitution Hall by the Daughters of the American Revolution organization in 1939, Eleanor left the organization in protest and helped organize a second concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Eleanor later introduced Anderson to the King and Queen of the United Kingdom after Anderson sang at a white house dinner. Roosevelt also lobbied the appointment of African-American educator Mary McLeod Bethune, with whom she established a friendship, as director of the Department of Black Affairs for the National Youth Administration. To avoid problems with the staff when Bethune visited the White House, Eleanor would meet her at the door, hug her and brough her in hand in hand.

She was considered the “eyes and ears” of the New Deal. She looked to the future and was committed to social reform. One of these programmes helped working women get better wages and not to work in the hard physical jobs in factories as they did during the war. Roosevelt’s, without precedent, introduced activism and the ability to actively perform socially responsible office to role of the First Lady.

United Nations

In December 1945, President Harry S. Truman appointed Eleanor as a delegate to the United Nations General Assembly. In April 1946, she became the first chairwoman of the preliminary United Nations Human Rights Commission. Eleanor became permanent chair when the Commission was established in January 1947. Along with René Cassin, John Peters Humphrey and others, she played a key role in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Her greatest contribution is evident in the swiftness of adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the midst of increasing antagonisms between the US and the USSR and the increasing heat of the Cold War, which has become a growing obstacle to the adoption of a declaration drafted, negotiated and voted in a record time of a year.

In a speech on the night of September 28, 1948. Eleanor gave a speech on the Declaration, calling it “the international Magna Carta of all people everywhere”, and the Declaration was finally adopted by the General Assembly on December 10, 1948. The vote was unanimous, with eight abstaining: six countries in the Soviet bloc, South Africa and Saudi Arabia. Roosevelt attributed the abstaining of Soviet blocs to Article 13, which ensured the right of citizens to leave their countries.

Author: Ivan Blažević, Secretary General