Written by: Zoran Pusić, retired university professor and human rights activist

I met Mrs. Desa Baković and her husband Jerko around twenty years ago. Beginning in the late fall of 1995, activists of the Citizens’ Committee for Human Rights visited deserted villages and small towns in Kordun and Bania to distribute food, clothing, household items, and medicine. We shared the supplies with the few, mostly older, people who had stayed after the “Storm,” some refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina, and, over time, returnees who often had nowhere else to go.

Most of what we shared was collected through donations from citizens. Jerko and Desa made contributions several times and invited many of their friends to join in giving aid.

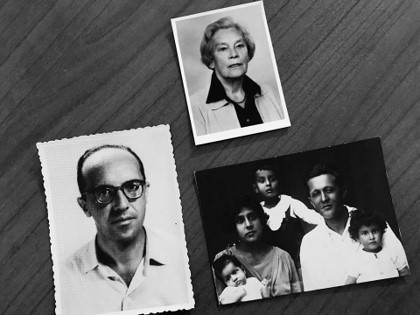

Their last name was associated with the Baković sisters, but, of course, it didn’t necessarily mean anything. However, as we came to know each other better, we found out that the Baković sisters were Jerko’s sisters, and we learned that this quiet, self-effacing, warm-hearted man had a life story resembling an action war novel.

About the Baković family

At the beginning of the 20th century, Jerko’s father Frane left his native Nerežišće on the island of Brač to live with his uncle in Bolivia. There he became a wealthy hotel owner in the mining town of Orur, where he got married and had five children: Ivan, Zdenka, Jerko, Mladen and Rajko. When the oldest children reached school age, the family decided to return to Croatia so the children could attend school and learn Croatian. The Baković family returned in 1921, first to Brač, where their son Davor was born, and then to Zagreb, where Frane’s father bought a house on Gundulićeva Street.

The rare and noble trait of helping others in need (which is also behind the decision of Jerko and Desa Baković to establish the Fund for the Education of Poor Children) was strongly present in the Baković family. Ivo, Zdenka, Jerko, and Rajka had a strong sense of social justice as young people, becoming anti-fascist oriented even as fascism grew increasingly prevalent and powerful in Europe. They first joined the work of SKOJ and then the illegal Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

Membership in the communist party sounds almost like an accusation in today’s Croatia. There are two reasons for this. One is that much more is known today about the crimes committed during Stalin’s or Mao’s rule, which almost all communist parties, in at least one period of their existence, idealized to the point of stupidity. The second is that the actions of every communist party, and even the idea of communism itself, are now uncritically identified with these examples of the degeneration of the one-party communist rule into cruel dictatorships.

However, membership in the KPJ before World War II was a status that did not carry any privileges but entailed real dangers. For many young people, this membership implied rebellion against existing social injustices, declaration of anti-fascism against intolerant nationalism and clericalism, and faith in a more just society.

At the end of the 1930s, after the sudden death of Jerko’s father, his mother Irma was left with six children and no steady income. The Bakovićs bought a small tobacconist on Nikolićeva street in Zagreb (the tobacconist was opposite the Vinodol restaurant), which served as the family’s only steady source of income.

After the establishment of the NDH and Ustasha terror government, the tobacconist, run by Zdenka and Rajka, became a point of contact with the Partisans. In December 1941, the Ustasha police caught a Partisan courier carrying some messages from Dalmatia; under threat of harm, he revealed the Baković sisters’ tobacconist as the place where he was supposed to deliver the messages. Both sisters were arrested and brutally tortured in the prison on what was then “N” Square (now the Square of Victims of Fascism). They were taken back to the tobacconist during the day so that the Ustashas could catch more of the illegal associates. Zdenka and Rajka, despite the torture, did not betray anyone.

One day, Rajka was brought to an apartment in Gundulićeva by Ustasha police agents. She managed to sneak a piece of paper to her brother Jerko on which was written: “They are torturing me terribly. May I speak?” Jerko wrote to her on the back of the piece of paper: “No.”

On Christmas Day 1941, according to the official police statement, Zdenka threw herself from the fourth floor of the UNS building, at the corner of “N” square and Zvonimirova. It has never been established whether the Ustashas threw her, or whether she jumped to escape the torture, or whether jumped in fear of betraying someone under torture. Rajka died three days later in Sveti Duh hospital as a result of torture.

In 1990, when the Square of Victims of Fascism in Zagreb was renamed the Square of Croatian Greats, I wrote: “In the history of a country, before all rulers and greats, come those people who stood up against darkness and tyranny when darkness seemed opaque and tyranny invincible. There were many such people among the victims of fascism.” Remembering and re-reading about the tragic fate of those young girls (Zdenka was 24 and Rajko 21 years old), both of whom were determined to fight for the values without which human society has no meaning and in whose defense anti-fascism arose, it seemed to me like a kind of historical justice that the square, where they and many other anti-fascists perished, was given back the name Square of Victims of Fascism.

Jerko was arrested in mid-January 1942, interrogated, and imprisoned in solitary confinement on “N” Square. From there he was sent to the Jasenovac camp. He survived by accident. When the Ustashas took him from the camp, according to his wife, he was convinced that he would end up like many others, killed and thrown into the Sava. However, the Ustasha exchanged him for an Ustasha officer who was captured by the Partisans.

Jerko remained with the Partisans until the end of the war. In 1945, Jerko went to look for his mother and brothers who had been scattered by the war, from the partisans to El Shat. He found his oldest brother Iva in Ruma, where he worked immediately after the war. There, Jerko met Desanka Bobić through Iva.

Desanka Bobić was born in 1917 in Dabro in Lika. Her family, as economic migrants, moved to Ruma. Having lost her father at an early age, Desa had no opportunity to continue her education. Instead, she helped her mother feed the family by sewing. The memory of her desire for education and inability to continue schooling followed her into old age and certainly influenced her decision to establish the Fund for the Education of Poor Children.

Shortly after meeting, Jerko and Desa got married and settled in Zagreb, where Jerko graduated from the Faculty of Economics and, over time, became a respected expert in banking.

Jerko Baković died in 2010 at the age of 95. A year later, Mrs. Desa Baković called me and asked me to help fulfill their wish that part of their property be used to help poor children, particularly in education. Mrs. Baković wanted to raise the funds by selling the apartment where she lived. I promised to help, telling her that it was refreshing to see someone wanting to help the poor in the midst of a society saturated with daily news about various “Superhikovima” who take from the poor and give to the rich, but we couldn’t start anything serious until the funds were there.

At the end of 2017, Mrs. Baković managed to sell the apartment on the condition that she use it for life. With the finances available, concrete steps could be taken to establish the fund and find the first beneficiaries. For help with the foundation, I turned to Marina Škrabalo, manager of Solidarna – Foundation for Human Rights and Solidarity, and her colleagues, people experienced with the functioning of foundations. Solidarna facilitated the establishment of the Desa and Jerko Baković fund, a dedicated fund for scholarships and assistance to poor children during schooling, with a separate account and a foundation council to manage the work of the fund.

The criterion for awarding aid from this fund was that the beneficiaries want to continue their education but cannot do so due to financial reasons. We obtained information about the children through teachers in student dormitories, teachers in primary and secondary schools, parents, and civil society activists. In the beginning, our goal was to choose a dozen children who desired to continue secondary education but were prevented financially; under certain conditions, we would finance four years of their education. Although the six thousand kunas donated by Mrs. Baković appeared initially to be a large fund, it results in modest scholarships that barely cover the most essential expenses when you divide it among a dozen children for the many years of schooling. However, when we read the petitions sent by the students themselves or their teachers–with stories about children whose parents live on social assistance, who walk tens of kilometers to school, who are victims of domestic violence–our ambitions grew and the foundation council chose thirty-one awardees between 8 and 18 years of age. The funds were sufficient to cover two years of education for the majority, and our decision put before the foundation council the task of collecting additional funds and donations to supplement Desa and Jerko’s donation, enabling the continuation of awards for those who received scholarships as well as for new scholarships.

*The above text is the speech of Zoran Pusić at the presentation of the Fund. The fund was presented at the House of Human Rights on April 19, on the 101st birthday of Desa Baković, with her presence, and with the presence of children who were awarded scholarships.

Support the Desa & Jerko Baković Fund and donate here.